Home »

Archives

Gaming for Info Lit Flow

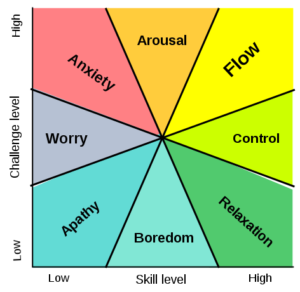

A few years ago Michael Waldman at Baruch Library was kind enough to recommend what he described as the least intimidating marathon training book, The Non-Runner’s Marathon Trainer, which introduced me to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow, as applied to long distance running. I learned that flow, an intense state when you’re fully engrossed in an activity, is usually attained when you challenge yourself to go beyond your skill level, but not so much that you’re intimidated (see graph).

Flow makes me feel radiant! So I look for opportunities to achieve flow whenever I can, whether it’s in my personal or professional life, including my teaching. In fact, I’ve noticed that some of the most memorable experiences I’ve ever had as a student were when I experienced flow in a fun and immersive environment through a creative assignment or a game of some sort – as part of a junior high school moot court defense team or as an adult learner when our teacher tested our class’s knowledge of a unit (on some rather dry material: intergovernmental legal documents) using a Jeopardy-style game complete with prizes! So, I have long believed in the power of gaming (table-top games, role-playing games, video games) for educational purposes.

And while I’m by no means immersed in the gaming world, I’m an advocate. A few years back, I was at a meeting where a student was demonstrating an online role-playing history game for a room of educators. I overheard one professor at my table privately question the educational merit of playing the game, which seemed to her to be a matter of mindless clicking to advance to another screen, with no intellectual rigor behind it. Sometimes when gaming is used in pedagogy, it’s frowned upon because there is an impression that it’s superficial or gimmicky. So I raised my hand and asked the student to explain whether players would need to have a foundation – to draw from a knowledge base – in order to make decisions about how to proceed in the game. He agreed that they did and explained how. The educator may not have been converted or even convinced, but I felt that gaming’s merit scored some points that day: games can enhance and foster learning by providing an engaging and relatable environment in which students can reflect on subject matter. And yes, games do provide opportunities for thoughtful, critical thinking.

In the fall of 2018, I used a mock trial role playing activity in my 3-credit freshman history course on the Conquest of Latin America. I hand selected student groups to represent five different defendants (Christopher Columbus, Columbus’s Men, The Crown, the Taínos, and the System of Empire) against the charge of the genocide of the Taíno population. What I thought would be a three-session activity turned into a four session one, and could have easily gone on for five or six. It was a remarkable experience for me. Some of the quiet students became very vocal during the mock trial and those who were typically talkative in class became even more impassioned. After one defense team stated their case, a student in the audience questioned them past the allotted class time. Some students with scheduling conflicts left, but about half the class intently and respectfully stayed behind until I had to cut the debate short because another class was scheduled to use our room. These markers of engagement made me feel that we had achieved “flow.”

One of the most enthusiastic students left an impression on me by telling me that she didn’t know whether I just had a keen eye for knowing which students would click, but she was very surprised that she wound up becoming fast friends with her teammates. While I’d like to take the credit, it was actually a lucky confluence: all the students were also registered in a second writing course, making them a learning community, so these friendships would have developed sooner or later as a matter of course. However, one thing is certain: this type of group work and role-playing game helped cement some of those relationships. So, I think another added benefit of gaming of any kind is that it can encourage dialogue and camaraderie.

Beyond all the intelligent, nuanced, incisive arguments and reasoning that went on during the course of those two weeks, I could tell that the students were also having fun. Students owned their personas and took pride in the arguments they would present. They created professional looking PowerPoints, used music, asked for audience participation, and they dressed up as King Ferdinand, Queen Isabella, and even the Pope! Playing makes learning more fun at any age and gaming is a great way to foster flow in our students’ academic lives as well as our own.

I was pleased, then, when I first came to CUNY and learned about The CUNY Games Network. I attended this year’s CUNY Games Conference 5.0 after a hiatus of a few years. It was a neat departure from the previous ones I’d attended, where the main presentation format was a panel or talk (the organizers had opted for this more participatory format before, but it was my first experience with it). I attended the “Redesign: Modifying Tabletop Games for Instruction” workshop run by Joe Bisz and Carolyn Stallard, where we played the games “Apples to Apples” and “Snake Oil” and later discussed their mechanics and how we could use these to enhance our own instruction. During our discussion, we brainstormed a possible modified version of “Snake Oil” for a history course: the cards could be different historical figures studied during the semester and the dealt cards could all include other historical figures or resources that could help the historical figure advance in the game. We did not work out the specifics, but it would be a great game to play at the end of each unit to help students reinforce their knowledge and help them become more conversant and confident with the subject matter.

In Bisz’s second workshop, we played his What’s Your Game Plan? A Game for Growing Ideas into Games, an actual table-top brainstorming card game available for purchase. We were asked to choose a lesson (normally, you would choose a lesson card in the course of the game) and we were then asked to create a game for this lesson using pre-selected cards that required us to use a specific game (Checkers, Jeopardy, Scrabble, etc.), mechanic (movement/sport, jumping, role play, etc.), and action (investigating, bluffing, trading, etc.). Each group at that workshop created the basic parameters of a game for different lessons in various disciplines.

My flow-like experience with the history course students and the brainstorming at these practical workshops renewed my interest in incorporating gaming into library instruction. If you feel that you can’t possibly incorporate a game into your library instruction because you don’t have the luxury of teaching a 3-credit class, you’ll be happy to note that librarians have shown that this is totally possible in a one-shot library class. City Tech Chief Librarian Maura Smale modified Bisz’s brainstorming game and Tiltfactor’s Grow a Game to come up with the open access Game On for Information Literacy, which has been used by CUNY librarians to create a game that could be used in one-shot classes learning MLA citation style. CUNY librarians have also created a rubric for different information literacy games that can help us as we create games of our own. Do you have or know of an info lit game that can be incorporated into a one-shot class that you’d like to share? Let me know (ddominguez@ccny.cuny.edu) and if there is enough interest, I can put together a gaming for into lit flow toolkit to share!

Transferring skills from arts ed to info lit

The last job I held before becoming a librarian was as a facilitator of arts programs, working 11 years for ArtsConnection, a non-profit that brought professional visual and performing (music, dance, theater) artists into public schools pre-K-12 throughout the five boroughs of NYC.

Each time I’ve changed careers, I’ve tried to carry over whatever I managed to learn in one field to the next. Here are four aspects of teaching that I came to value in arts education that have proved useful guideposts for me as a teaching librarian at Hostos Community College. I hope they may be of some use to other teaching librarians as well.

(1) Collaborative teaching partnerships

Then: Although we provided a diverse range of in- and after-school instruction, the most common project was a 10-session residency of workshops held once a week, in class, with the classroom teacher present as the artist taught.

Classroom teachers often had limited or incorrect assumptions about what our teaching artists, as visiting instructors, could offer their students. They didn’t want their time wasted.

Given our brief stays in each school, it made a huge difference when teachers saw the worth of our programs. An engaged teacher helped students make connections between learning in the arts workshop and learning in the classroom, even if there was not a direct curricular connection, and their very engagement gave students the message that the work in the arts was an important part of the school day.

Deciding to be an at least watchful or even enthusiastic presence during the workshop also gave classroom teachers an opportunity to learn more about their own students. Teachers often told us how their perception of a given student’s ability (to concentrate, take risks, create, inspire others, work toward a goal) was transformed by watching the student learn in the arts.

Planning and goals

The first step to getting teacher buy-in was our planning meetings. The classroom teachers and the teaching artist often started out with different vocabularies regarding student learning, and my job as facilitator was neither to force the artist into edu-speak nor to force the classroom teacher into artist-speak, but to help bridge a common understanding and shared set of goals.

Some (certainly not all) teachers, under tremendous pressure to raise English and math test scores, were reluctant to “give up time” and assumed that the arts work would at most give students a chance to blow off steam and have fun. Planning meetings allowed us to show how learning in the arts would help students build both particular skills within the art form and broader skills such as problem-solving, empathy, collaboration with peers, public expression, and creative discovery.

It’s not that teachers didn’t want those things, but they weren’t (usually) artists, and we couldn’t assume that they would see or articulate such goals spontaneously before the workshops, or see exactly how the arts could bring such learning to their students.

Laying the abstract groundwork of goals was always important, but the real buy-in came when teachers saw their students learning in the moment. When teachers saw students engaged with something worthwhile, they were won over to working with the teaching artist as partners.

Now: Although academic librarians provide a diverse range of instruction, through workshops, reference interactions, consulations, online guides, and semester-long courses, our most common method of instruction is the one-shot workshop to support a course’s research assigment.

Professors in the disciplines often have limited or incorrect assumptions about what we librarians, as visiting instructors, can offer their students. They don’t want their time wasted.

I’ve found that professors who aren’t just grading papers in the back but actively observing and engaging in the research workshops (such as circulating as I do as students work in small groups or on their own) help students make connections between what they’re learning in the workshop and their classroom learning. Professors’ engagement sends the message that the library workshop is an important part of the course.

I have also seen observant professors change their understanding—not as much about their students’ abilities, but about the reality of how students grapple with their research assignment, or still have questions that the professor thought had been made clear in class. These observations help us in our discussions as we evolve our teaching partnership in subsequent semesters.

Planning and goals

In initial planning conversations, we often start with different perspectives and ways to assess student learning. Some professors may be reluctant to “give up time” and assume that all a library workshop could do is introduce students to the existence of EBSCO. Well-meaning professors who start conversations with a request to “teach them how to cite” or “how to use the databases” or even “how to research” as if that were a 75-minute task, remind me of those K-12 teachers who hoped that dance might somehow improve math scores. What they’re really saying is: please do something with my class that will be of use to them, and here’s what I assume that help might look like.

Just as we librarians shouldn’t always take a student’s opening query at a reference desk at face value, but instead use a patient, listening, probing reference interview to see what it is they really want and what might help them more, I believe that these opening queries from professors offer us a similar opportunity to start a real planning dialogue.

Communicating goals in advance helps lay the groundwork. As teaching librarians, we know it’s not just being able to navigate a proprietary interface that counts, it’s a myriad of understandings, whether captured by the abstract intellectual concepts of the Framework or the liberating perspectives offered by critical information literacy; it’s also learning concrete skills and habits such as developing a focused inquiry as a more propulsive start to research in place of an overly broad topic, or distinguishing between kinds of available sources and learning how to use them strategically instead of haphazardly; it’s acquiring habits such as browsing the stacks because it turns out that books are organized by subject, or questioning every website they come across by asking, okay, who wrote that, what’s their agenda, and why should I believe them?

It’s not that professors don’t want these things, but they often aren’t thinking about all the particular elements of research that students confront. We can’t assume that most would articulate such goals spontaneously before the workshops, or see exactly how engaging in a research workshop could bring such learning to their students.

The real buy-in comes when professors see their students learning in action. The more they see students engaged with something worthwhile, the more they are won over to working with us librarians as partners.

(2) Learning through authentic experiences in the discipline & student voice

Then: I learned that students’ being active in class is necessary but not sufficient for learning. When students had an authentic experience in the arts, going through real steps of experimentation, making choices, stepping back to assess, revising, and innovating further—rather than following pre-ordained steps to creating a product–their learning was much more meaningful. Those residencies that most allowed for students’ original vision to guide the project and for their voices to shine through were inevitably more powerful than a slick, more teacher-directed project.

Now: What are the authentic experiences in research? If we show students the library’s discovery layer or a database and indicate how to click a couple filters, but the student just prints out the first five articles whose titles happen to echo their keywords, we know that’s not engagement in an authentic research process.

As Anne Leonard said here in an earlier blog post, the complex and iterative process of research is something learned over time, and often students are still growing out of a conception of “research” as a quick looking up of set answers to imposed questions. Authentic research processes of defining their own inquiry, searching, selecting, reading, discovering new ideas and developing new questions, reframing their inquiry, and so on, are new to many of them.

The extent to which we can influence the structure of a research assignment varies wildly and we of course can’t force students to engage deeply. I’m also aware that our students at Hostos are often juggling work, family, and other obligations, and understand that not every single research project will pull in 100% of their effort.

That said, whether in workshops, at the reference desk, or in one-on-one consultations, we can ask them to do more than follow our examples of where to click on a screen, and can directly address the progressive nature of research and the idea of searching as strategic exploration.

Helping students follow their own paths through their research also means helping them understand good places to start, and showing them how to strategize their search, for instance knowing when they would be helped by first reading background texts to be able to confidently engage with more scholarly sources. We can to the best extent possible help students take as much ownership as a given assignment will allow.

(3) Big picture learning while planning the particulars

Then: The teaching artists we worked with were required to write out their plans for a residency, including learning goals. Some viewed this process as paperwork or as restrictive, but many came to value the reflection demanded by posing the questions: what do I want students to know and be able to do after this lesson? What are the larger understandings in the art form that they will start to build?

Writing out a lesson plan also helped artists determine the scope of what they could do, given the limited number of minutes and days in a residency.

Now: Although I don’t start out with the Framework as a base for workshops, I find that its larger understandings often slide organically into lessons. Here are just a few examples:

- Media literacy workshops offer obvious opportunities to address the idea of authority as constructed and contextual, although I also touch on this idea in workshops in which students engage with Library of Congress call numbers, noting that although it’s useful for students to be able to navigate this system, it was created by a specific institution in a specific historical context and certainly has flaws that we can critique.

- Any mention of needing to sign in with a CUNY ID in order to get access to database articles off-campus is an opportunity to show that information has value and that access is limited because of the way that publishers make money and that educational institutions comply.

- When students say they already know exactly what their paper will say before having read any “sources to cite”, we can raise the idea of research as inquiry and of discovering new ideas. Two informal writing prompts I use in many workshops are “what are some things you already know about your research topic?” and “what do you want to find out that you don’t know yet?” These are simple questions, but kick off discussion in which we address the idea that the research process is not just about looking up people who reiterate what you already think.

- Often in workshops, I’ll address the fact that they will encounter equally qualified and credible writers who sharply disagree on a subject, and that part of the students’ work as researchers and writers is to grapple with those arguments—understanding that scholarship is conversation, not just a canon of obvious, universally accepted, and unchanging facts.

Writing out lesson plans also helps me see what I can accomplish in one workshop. Sometimes I have heard librarians say they don’t have time for the bigger picture, but in writing down my exact plans, I have found not just things that need to be cut (I think a common librarian urge is to try to say too much), but also natural places for just raising questions and planting seeds; a lengthy exercise or discussion is not always necessary to integrate bigger-picture ideas.

(4) The importance of a teacher’s energy

Then: Although I had known this from many years of being a student, observing dozens of teaching artists each year and clocking literally thousands of hours of observation over the course of a decade showed me over and over that the energy you put out as an instructor is the energy you get back.

Now: I have seen some librarians and some professors who whether from shyness, self-consciousness, or perhaps a feeling that it is more authentic, teach with the same voice they might use in a one-on-one conversation, or in a small group meeting. In these cases, the energy and attention of students tend to untether and drift out of the room.

As for nerves, something I learned previous to my last job was that jumping in with gusto burns off much of the nervous energy, and the attentive response you get in return kills off the rest. As for the desire to remain authentic, I have found that after a while, your heightened “teacher voice” is just another equally authentic version of yourself.

Although I’m certainly not as skilled as a professional actor, I channel as best I can the kind of enthusiasm, responsiveness, and direct engagement that I loved in our most effective theater teaching artists, and I usually get great energy back from students. If I’m tired or if it’s the third workshop in a day, I can feel my lower level of energy and a corresponding drop in the room, so I know it’s not just the lesson plan that makes a difference.

Although my lesson plans focus on what I want students to learn and be able to do, right before every workshop I stop and ask myself (knowing I may be distracted or stressed with other worries), “How do you want the students to feel?”

This question forces me to remember that I want students to feel happy to be there, welcomed, excited about learning, and confident that they will be able to take charge of their research–and remembering that helps me to walk into the room with energy that reflects those aspirations.

The Power of PowerPoint

Alright, maybe it is not that powerful, but at least, useful.

In my college days, professors’ lectures were mostly verbal and sometimes aided by a blackboard. The professor would either talk my head off throughout the whole lecture non-stop making me take notes busily in the fear that I might otherwise miss some important things, or in a better situation, write some key points on the blackboard with a chalk but I, occasionally if not often, had to do a guess work due to an individualized handwriting. Sometimes, the professor might use a slide projector making things a little better, but I still struggled with the handwriting on the slides. I never had a class that featured in PowerPoint presentation because that was in the last century, a long time ago before PowerPoint came into common use in classroom teaching. Thanks to technology that makes teaching both verbal and visual.

My first attempt to use PowerPoint was in 2002 when I was engaged in a summer teaching exchange program between CUNY and Shanghai University in China. The two courses that I taught, Introduction to Information Sources & Services and Using the Internet for Research, had two hundred students in each. Class size was incredibly large compared with the American’s (we have an average class size of 25 at York), partly because the students were interested in the course contents (and partly … hey, it’s a populous country.) The classes would be held in a large lecture-hall and I would have to use a microphone to deliver lectures. All seemed okay except it might be difficult for students sitting in the back to take notes from distance. Then I discovered that the room was equipped with a computer and a projector for the lecturer. I decided to try to use PowerPoint instead of using a traditional blackboard. However, I was a novice user and knew little about the software. Fortunately, my teaching assistants, assigned by the university, were tech savvy. They taught me the basics and showed me some useful tips. (Off the topic: they also helped me “climb over the wall” because some databases and websites were blocked by the so-called “Great Wall”, a government-backed internet filtering system, but I needed to use them for classroom demonstrations.) All lectures went smoothly and the university was pleased to see the students learning outcomes. Since then I have used PowerPoint frequently.

It must be stated that I am no expert in the full spectrum of PowerPoint universe but a happy user of it. In my practice I enjoy the following benefits from using PowerPoint to teach one-shot library workshops.

It is visual

In addition to our talking, students can enjoy the graphs, diagrams, tables, images, and photos that are visually descriptive in effective ways. Thus, the students can get a better understanding of our points.

It is multimedia

We may use Animations, Transitions, Audio and Video files to enhance the presentation and to enrich user experience.

It has multiple usages

We can save the PPT file as PDF and make it handouts for students to use during the session and/or for future reference.

It makes it easier for students to take notes

Students never need to guess what’s on the projected screen since the text is typed.

It is more than a local file

We can hyperlink reference databases and websites to introduce sources from our library’s subscribed databases and on the Internet, and access relevant information with a click of the mouse.

I also recommend the following tips.

- Use large fonts for both heading and text for easy reading.

- Use timed presentation if you are good at time management.

- Use click-controlled presentation if you want to have more control over slides.

- Don’t use the background color that is too similar to the text color.

- Don’t use too much text on a single slide.

Attached here is a sample PPT file which I use for orientation workshops.

Searching as strategic exploration: towards an embodied information literacy

As instruction librarians, we know that the iterative, sometimes nonlinear, search process is an expert searcher’s ability; it comes only with practice and through experience. Yet novice researchers – undergraduate students – may not yet have had this experience and practice. Consider how students could embody information literacy. Students embark on metaphorical journeys in the search for more, and better, information on a topic. In the search process, students circle back to their keywords, explore new disciplinary frontiers, cross thresholds, and reiterate their search strategies to become ever more confident and competent in a new domain of knowledge. Walking, journey, and travel metaphors can be found everywhere in higher education. CUNY’s general education framework is called Pathways. We speak of the pursuit of knowledge, of a student’s path to graduation, and of degree mapping.

What if we put metaphors aside and documented (mapped) the progress of searching as strategic exploration? Consider students’ lived experience. They all bring with them embodied knowledge that is located more in the realm of intuition and insight. What if we helped students discover their embodied knowledge through reflecting on this iterative process of searching? In your next one-shot, consider asking them to uncover knowledge they already possess by posing one-minute paper prompts such as, “What was your a-ha moment (or challenging moment) in today’s class, and why?” or “How can you apply what you learned in future research?” This generates a map or milestone in the student’s journey to information literacy.

While I have found that a reflective and creative approach to the frame searching as strategic exploration valuable in my information literacy and library instruction work, I recognize that it is not the only frame. It was not even the frame that initially resonated with me. I’ve come to realize that there is great value in doing a deep dive, or taking a long walk, with one frame. Whatever frame you choose, make friends with it. Consider yourself in a long-term (though perhaps not exclusive) relationship with it. You just may find yourself drawing on your deep knowledge and familiarity with that frame extemporaneously, particularly in those instruction sessions that do not go according to the lesson plan.

Thoughts on reflection prompts and questions you’ve tried, or would like to? Leave a comment below!

A few suggestions for further reading:

“Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), 9 Feb. 2015.

Kerka, Sandra. “Somatic/Embodied Learning and Adult Education.” Trends and Issues Alert. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, 2002.

Spatz, Ben. “Embodied Research: A Methodology.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 2017, pp. 1–31.

What does a librarian teach?

- Authority as Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

As you can see from this list, information literacy has been recast as being about ideas. How is authority defined? How do we think about information? It takes real work to integrate these ideas into the day-to-day work of a growing one shot program. I appreciate that it gives a target to shoot at.

A teaching librarian fails at summer vacation

It’s August and I’ve been reflecting on whether I’m making the most of the quiet summer months in our academic library. I’ll confess that I approach summer “break” with an aspirational attitude similar to the one that sparks New Year’s resolutions. And yet, come August, I annually feel panic about whether or not I’ve made the most of my summer. As the academic year ends, I begin to create my mental list of summer projects, things like catching up on reading, cleaning off my desk, planning for the coming year, and working on becoming a better teaching librarian, all before the new semester starts. In past summers, I’ve really emphasized that last one — become a better teaching librarian — leading to unnecessary pressure, and unexpected results.

In May 2017, for example, I attended LOEX for the first time. I returned to my library buzzing with new ideas to improve my practice. When summer rolled around, I decided to turn those ideas into a single project: developing a lesson plan around strategic searching, which I am frequently called on to teach. This lesson would be different from those lessons that I rush to put together during the semester. With this lesson, I would be more deliberate in my teaching. A pre-made lesson would also streamline my practice for a busy fall. Finally, with the extra time, I could focus on the areas where I had seen students struggle in the past year.

I optimistically estimated that the resulting lesson, a script for me and a two-page worksheet for the students, could be taught in 75 minutes. Ha! I never found out as I was too daunted to try it. Initially, I told myself that the lesson wasn’t a good fit for the particular classes I was teaching. Revisiting the lesson to write this post, I see now that it was much too complex and not at all appropriate for a one-shot. More likely these exercises would have taken at least two class sessions to do well. Having put in hours of work with little to show for it, my big summer project felt like a colossal failure.

There is a happy ending, though, as I’ve learned several valuable lessons from last summer’s experiences. First, summer is not the best time (for me, at least) to develop my teaching because I’m not actually working with students. My lesson plan was not coming from an authentic place; it was developed for imaginary, idealized students. However, revisiting the lesson, I now realize that I have incorporated some elements of it into the lessons that I developed during the academic year. The thinking was useful, even if I couldn’t use the original product. Finally, I’ve changed how I think about summer. This year, I have spent my time catching up on reading and doing some much-needed writing. I’ll save the actual lesson plans for the semester, when the ideas of the students are much closer.

What New Things Can I Do?: The Roles and Strengths of Teaching Librarians (ACRL, 2017)

Taking a bit of time this summer to catch up on my professional reading, particularly as it relates to instruction, I once again happened across The Roles and Strengths of Teaching Librarians (approved by the ACRL Board of Directors, April 28, 2017). I had observed the advent of this reimagining of the 2007 Standards for Proficiencies for Instruction Librarians and Coordinators a little more than a year previously, while in the throes of an end-of-semester blur, but at the time I had filed it away as something to come back to when I could afford it closer attention.

The document describes shifts in thinking about teaching in libraries, precipitated in part by the shift from Standards to Framework in thinking about what and how we teach. Our profession has seen a rapid evolution of skills and responsibilities, and there was a desire to articulate a perspective inclusive of the broader range of work that is being done, the variety of institutional contexts, and the different ways we practice teaching-related work in libraries across our careers. The new document provides a conceptual model of seven roles, and a description of the strengths a librarian might need in order to thrive in each of those roles: advocate, coordinator, instructional designer, lifelong learner, leader, teacher, and teaching partner. The document stresses that these roles can and often do overlap, that individual librarians may find they identify with some of these roles more strongly than with others, and that it is not necessary (and may even be a little crazy to think) that any one librarian would or should possess all of them.

The document suggests certain benefits to this re-conceptualization. If you’ve ever found it challenging to describe the sometimes unique and somewhat abstract teaching work you do, this new model may help you name, describe, and situate your practice relative to the other work of the academic enterprise. Four to eight strengths are listed relative to each of the seven roles. For example, as a teaching partner, you may “[bring an] information literacy perspective and expertise to the partnership,” and as a lifelong learner, “[actively participate] in discussions on teaching and learning with colleagues online and in other forums.” If one goal is to be able to think about and talk about the myriad ways we support learning in libraries, this tool has a lot of flexibility. However, the idea that struck me most in reviewing the document is the notion that, with a reinvigorated and perhaps clearer conceptualization of the teaching-centered practice of academic librarians, we might ask ourselves the question: what new things can I do? As acknowledged by the framers, this document is both reflective of actual practice and aspirational.

As a bonus, I also found myself interested by the process of the revision task force – how they actually arrived at the conceptual model, roles, and strengths. So I encourage you to take a look, if you haven’t already. There’re still a few weeks left before the end of summer and the beginning of chaos.

4 Reasons Why You Should Keep a Reflective Teaching Journal

Back in January, I was casting about for some instructional inspiration. What could I do, what could I try to improve my teaching in the upcoming semester? A light bulb went off when I suddenly remembered Betsy Tompkins’ (2009) excellent article on reflective journals. She suggests that the systematic practice of recording teaching processes, decisions and behaviors may be “a source of inspiration and professional development” (Tompkins, 2009, p. 232) to academic librarians. Motivated by her example, I experimented with a reflective teaching journal during the Spring 2018 semester and was delighted with the results. Below are my four best reasons why you might consider keeping one yourself.

- Cheap and easy

No need to register for another expensive webinar or workshop. This professional development opportunity will cost you nothing more than a bit of time and effort. To get started, all I did was set up a journal entry template in Word, modifying Tompkins’ (2009) form to include sections on materials, assessment and future planning. Over the course of 15 weeks, I used this template to create entries on 25 one-shot sessions. I’ve included my template in this post as well as a sample entry prepared for a BU401 Elements of Marketing class.

Typically, I would fill in a template through the “Summative Assessment” section before the class meeting; this act of writing actually enhanced my lesson planning. Then I tried very hard to complete the “Post Class Reflections” and “Link to Future Planning” sections immediately following the class. The latter didn’t always happen, but I found I generated much better insights when I journaled right away.

- Good data

A teaching journal can help remind you what to do different and better the next time around. Recently, I was asked to teach a summer section of Elements of Marketing with two days’ notice. I pulled out the Spring 2018 BU401 journal entry below and was immediately reminded to update my materials with the new textbook title and with a U.S. Census citation demonstration.

I am hopeful that my journal notes will also inform conversations this fall with returning classroom faculty. Rather than passively accepting incoming instructional requests, I now feel equipped to initiate specific recommendations and suggestions. Two possible examples include:

- “Follow up with (professor’s name) re books as sources conversation. If in fact he does link book use to better papers, perhaps we can devise an assignment whereby students locate and engage with one book related to “Exit West” themes.”

- “It was progress that she included a graded assignment related to the library session. But maybe going forward, we could push beyond finding the article and add on reading/understanding the article. I take responsibility for that, and will be more assertive going forward.”

- How am I doing?

A lot of my entries are pretty basic, like “I was flat today” or “This lesson plan has too much content” or “Consider eliminating the research question video.” But in February I wrote up an experience which I am still thinking about. A student stopped me after class and said: Excuse me, professor. I hope you don’t mind me asking. How do you think you did today? I was startled and amazed by his question. When I asked if he wanted to give me any feedback, he shared: You are too comprehensive. Students are not robots. Just say – there’s information out there if you want it. And you know what, he is right! I sometimes worry so much about clarity and connecting the dots, that I often do not leave space for trust and discovery. Journaling helped me to process this truth and has helped kept this experience front and center all semester.

- Teaching artifact

An academic librarian can use a reflective journal to improve her teaching. She can also use it as an artifact of her instructional efforts. I plan to print all my Spring 2018 entries and organize them into a notebook, which I will then deposit into my Queensborough personnel file. That journal is a detailed record of my teaching activity; and while it may not hold the same currency within CUNY as student evaluations and classroom observations, it does provide authentic evidence of my commitment to teaching and learning.

Reflective Teaching Journal – Template

Reflective Teaching Journal – Sample

LILAC Spring Training RSVP

LILAC Spring Training: Up Your Game!

Practical Innovations Beyond Traditional Information Literacy

Friday, June 8th, 2018 | 12:30 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

CUNY Central | 205 East 42nd Street Room 818

The LILAC Spring Training is an afternoon filled with presentation pitches, a facilitated group activity, and more. Presentations, discussions, and workshops of various lengths will be divided into three tracks. During the first session, all participants will have the opportunity to sign up for an individual track after learning more from each presenter about their session.

RSVP is required by June 1st due to building security.

Space is limited.

Light Refreshments will be provided.

Tools/OneSearch

- Using Google Docs and WordPress for Communication and Instruction

Sarah Johnson and Mason Brown, Hunter College - Encouraging Student Engagement in the Library Classroom with PollEverywhere

Emma Antobam-Ntekudzi, Bronx Community College - Not teaching OneSearch is No Longer an Option

Marta Bladek and Maureen Richards, John Jay College - Using OneSearch: Librarians Need to Stop Worrying, Our Students Like It

Anne O’Reilly, LaGuardia Community College

Engagement

- Strategies for Embedded Information Literacy Instruction for English Language Learners

Clara Y. Tran, Stony Brook University, and Selrnsy Aytac, Long Island University - Dis/Information Nation: Voter Personas and Dis/Information Literacy in the 2016 Election and Beyond

Iris Finkel, Hunter College and Lydia Willoughby, SUNY New Paltz

Evaluating Sources

- Navigating between Trust and Doubt on the Internet

Linda Miles and Haruko Yamauchi, Eugenio Maria de Hostos Community College - Understanding Fake News by Teaching with the Game Factitious

Sharell L. Walker, Borough of Manhattan Community College - What Do You Meme it’s Not Credible? Using Memes to Counter Misleading Information

Christina Boyle, College of Staten Island

The Library Information Literacy Advisory Committee, LILAC, is the Library Discipline Council of the City University of New York. All librarians inside and outside of CUNY are welcome to attend the Spring Training.

LILAC Spring Training Committee:

Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz, co-chair

Daisy Domínguez, co-chair

Anne Leonard

Linda Miles

Robin Brown

Julie Turley

Jonathan Cope

LILAC (UK) 2018 Conference Roundup

I recently attended the 2018 LILAC Conference in Liverpool, England. The conference is organized by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) information literacy group, so they are a bit like LILAC’s sister organization across the pond! There were some fantastic presentations that offered innovative ideas, creative ways to teach IL skills, and many exciting insights about our profession in the ever expanding digital environment. The following are some of my highlights…

Information and Digital Literacy at the University of Sheffield

The librarians from the University of Sheffield described their three year project creating an information and digital literacy (IDL) framework at their institution. The framework echoes ACRL’s framework and threshold concepts, and works to employ active and engaged learning aimed at creating information and digital literate students. The six frames include: discovering, understanding, questioning, referencing, creating and communicating. The literacies help students develop the skills throughout the curriculum and progress from novice to expert during their academic career. The university recognizes information and digital literacy as one of its core graduation qualifications (so lots of buy in) and a means to help provide students gain the necessary skills to be successful in an ever changing digital environment. This fascinating project aligns well with our own mission as information professionals! Want more info? Check it out here!

What Does Embedded Even Mean?

The librarians at the University of Leeds discussed their practice of embedded librarianship and the multiple and unexpected opportunities that arose across campus and within the community. Their presentation offered ideas and inspiration of how to become better embedded and showcased how they embed information literacy skills within course delivery. Examples included: collaborating with nursing faculty in developing and delivering academic assignments to nursing students, offering library support for employees who are part of the university’s local business partnerships, sharing teaching methods with the local National Health Service (NHS) libraries, and supporting students in publishing Open Access journals. The wide range of examples demonstrates the problematic nature of defining what we consider to be ’embedded’, but, it also serves as inspiration that we can embed ourselves across a wide range of places we may not had previously considered, reconsider our pedagogy, and engage students in innovative ways.

Librarians and Students in the Digital Landscape

In his keynote presentation, David White from the University of Arts London, discussed the ‘dataself’ or the ‘technoself’, and how it is essential when teaching students that we position them as a central in their own digital environment and experience. He touched on notions of critical pedagogy in teaching students how to navigate the complexity of the digital environment and expressed great insight into how essential our mission is as informational professionals and librarians. Supporting this mission helps students learn how to navigate the digital landscape, critically question the information that they discover, and learn to maneuver within this stratosphere. As such, we help students understand that the data and information that they interact with impacts their interwoven self-identity. Check out his keynote.

CILIP Redefines Information Literacy

On the final day of the conference, CILIP released a revised definition of information literacy:

Information literacy is the ability to think critically and make balanced judgements about any information we find and use. It empowers us as citizens to reach and express informed views and to engage fully with society.

The revised definition addresses how the theory and practices of information literacy has changed since 2004. In rethinking the definition, they considered the impact on Higher Education, but additionally on all individuals using information. The new definition contains four elements: a high level definition, a secondary statement, contexts, and the role of information professionals. Read more about it here!