Home » General (Page 2)

Category Archives: General

LILAC in 2020 / Welcoming 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic would forever change the way librarians live, socialize, work and teach. Prior to March 16, 2020, I remember a life that was made up of commuter traffic, in-person meetings, and face-to-face time with students and teaching faculty. Soon an emerging virus would became deadly and very quickly the stay-at-home orders were initiated. Everything changed.

The remaining months of spring 2020 became a semester consumed with figuring out each day while thinking about how best to move forward. CUNY Librarians worked swiftly on plans to provide all our services 100% online. It felt like a scramble to quickly adjust professionally and personally in this new normal. Just as other CUNY groups, LILAC and its members navigated teaching information literacy fully online. Our meetings were a break from the overwhelming transition. Throughout the spring they continued to be a place for us to share ideas, see faces and discuss online instruction success and failures. By the end of the semester there was a palpable collective exhaustion. We decided to scrap plans for a traditional Spring Training; instead we imagined a spring event that would allow the CUNY community to reconnect and reflect on an unprecedented semester.

This two day event took place on Thursday, June 4, 2020 – Friday, June 5, 2020. Attendees were given the opportunity to be part of conversations on asynchronous instruction, synchronous instruction, outreach and access. Small groups were facilitated by LILAC members and everyone was encouraged to reflect on their experiences. The event showed how much we had in common. We learned that consistent synchronous and asynchronous instruction requires a lot more work ahead of time. We learned that CUNY Librarians trained themselves those first few months. We utilized familiar tools while incorporating new ones (usually free online tools). Outreach became more about building relationships. The challenge was in keeping the Librarians’ availability “visible” to students who no longer see us on a daily basis. During the accessibility session, many understood the necessity of implementing universal design principles into online instruction material. Notes from the session reveal Amy Wolfe’s (CUNY Central’s Accessibility Librarian) Accessibility Toolkit was especially helpful.

By the fall, we were more prepared. Some of CUNY’s IT Resources for Remote Work and Teaching provided online conferencing options, some video creation, and editing tools. Similar to all other committees and groups, LILAC currently functions completely online. In-person presentations are now virtual and thanks to Linda Miles (Hostos Community College), Ian McDermott (LaGuardia Community College), Robert Farrell (Lehman College), and Christine Kim (Queensborough Community College) we’ve had a great start to the Instruction Chats. We look forward to sharing these recaps with the CUNY Community via our blog. We enter the new year more seasoned and with an openness to keep learning. We are committed to continuing to foster information literacy throughout the CUNY community in our new normal. We will continue to provide a space for members to share teaching materials, tools, and tips for remote instruction. There remains much uncertainty but our resilience proves the adaptability of information literacy.

This year LILAC is proud to work alongside ACRL/NY’s Information Literacy/Instruction Discussion Group and METRO Reference & Instruction Special Interest Group (SIG) planning the Critical Pedagogy Symposium. This major event will take place on May 17, 2021 – May 19, 2021. It will replace LILAC’s annual Spring Training.

We are in this together and you are invited to step into a bright future with LILAC.

Spring Training Reports – Final Installment

Here are the last reports from the 2019 LILAC Spring Training. Looking forward to a great new school year with everyone!

Culturally Responsive Teaching through the Intersectionality of Collection Development and Information Literacy

Presented by Madeline Ruggiero, Queensborough Community College

Blog post by Linda Miles (Hostos Community College)

Madeline Ruggiero discussed the rationale and strategies for including exploration of materials from the library’s print collection within information literacy instruction. Over time, Madeline has been augmenting the library’s collection with student assignments and common topics in mind, topics that often reflect students’ own cultural identities. She has built print collection exploration activities into her lesson plans, including searching for, retrieving, and navigating within books to identify additional sources or related lines of inquiry. These materials enrich students’ research exploration, heighten engagement, and highlight the excellent print collection of the library.

Google Forms: Differentiating Instruction, Condensing Feedback

Presented by Danielle Apfelbaum (Farmingdale State College)

Blog post by Linda Miles

Danielle Apfelbaum presented a novel method for using Google Forms to accomplish two goals: to differentiate instruction and to manage instruction feedback data from classroom faculty. First, she takes advantage of the branching function of Google Forms, initially asking students to self-assess their knowledge or preparedness for the assignment at hand. Depending on how an individual student responds, the form then asks them to complete a developmentally appropriate hands-on task and enter a response. Student who indicate that they are totally confused by search interfaces would be given a different set of instructions than that given to students reporting a great deal of prior success using library search engines, with each set tailored to their respective level of experience.

Danielle asks students to provide their names to motivate compliance, and, as their answers are submitted via the form, she displays a spreadsheet with those responses (without names) to the class. Since many activities require students to provide URLs to resources they have found or even permalinks to search results, Danielle is able to use these to help guide class discussion.

To manage faculty feedback data, Danielle uses the “use existing spreadsheet” function in Google Forms to collate into one spreadsheet the responses to separate forms, which are each specific to a given faculty member/course section. This keeps all the data together in one place, and allows her to do some cross-section or cross-departmental analysis.

Spring Training reports – part III

Today we present the third installment of reports from the 2019 LILAC Spring Training.

MoneyBoss Workshops – Financial Literacy for Community College Students Through Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Presented by M. Anne O’Reilly (LaGuardia Community College)

Blog post by Susan Wengler (Queensborough Community College)

Building credit. Managing student debt. Preventing identity theft. These are just a few of the many financial challenges facing college students today. During this detailed and engaging training session, Prof. O’Reilly described how LaGuardia’s Library Media Resources Center helps its students meet and master these challenges through MoneyBoss, a popular workshop series designed to strengthen financial competencies and knowledge.

LaGuardia typically offers six MoneyBoss workshops per calendar year; their 2018-2019 topics included:

• Starting a Home-Based Business

• Getting Control of Your Credit

• Tax Reform – New Tax Law Changes

• What You Need to Know to Start Your Own Business: First Steps

• What I Wish I Knew About Student Loans

• Identity Theft

Prof. O’Reilly shared specific tips and tricks for librarians and libraries interested in launching financial literacy programming:

• Partner: At LaGuardia, MoneyBoss is co-presented by the Library Workshop Committee, the Business and Technology Department, and the Social Science Department. Cross-campus collaborations have resulted in increased institutional support and visibility.

• Partner Some More: These one-hour workshops are taught by library faculty as well as classroom faculty and community partners. Prof. O’Reilly sends a call for proposals out to all LaGuardia faculty, thereby expanding both topic ideas and perspective; she has also brought in presenters from the Small Business Development Center and the Municipal Credit Union.

• Brand: She recommends branding your workshop series with a catchy name, e.g., MoneyBoss; she also suggests creating a program logo and flier template to be used in all promotional activities.

• Find Built-in Audiences: At LaGuardia, all Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) students are required to attend two campus events each semester; therefore she works closely with her ASAP office to ensure those students are aware of the library’s offerings. When feasible, MoneyBoss workshops are scheduled during the participating faculty’s class time; participating faculty can require their students to attend workshops as a classroom activity.

• Streamline Registration: LaGuardia students pre-register for MoneyBoss workshops through the workshops’ research guide: https://guides.laguardia.edu/moneyboss

• Incentivize: LaGuardia provides snacks to MoneyBoss attendees; a financial literacy-related book is also raffled off at the end of each workshop session.

• Assess: After the workshop presentation and before the book raffle, O’Reilly asks attendees to complete a satisfaction survey, which is distributed in paper format. Since 2017, 565 students have attended MoneyBoss sessions; of those students completing a survey, 85% rated the sessions as very good or excellent.

For more information on financial literacy programming, please contact Prof. O’Reilly or visit LaGuardia’s MoneyBoss research guide.

Mindful Movement and Breath Work for Everybody & Every Body

Presented by Anne Leonard (City Tech)

Blog post by Meagan Lacey (Guttman Community College)

For a variety of reasons—repetition of lessons, disinterested students—teaching librarians often report burn-out. Burn-out, resulting from chronic workplace stress, creates feelings of exhaustion that can negatively affect job satisfaction and performance. For this reason, Anne Leonard, Associate Professor at City Tech and certified yoga-instructor, led a class full of teaching librarians (many of whom were burned-out) through a 40-minute sequence of gentle stretching and breathing in order to help them calm and refocus their attention and energy on the present.

All exercises were performed while seated in a chair or by using a chair for stability so that librarians could practice these movements in their office and make time for mindfulness in the midst of a workday. During the discussion that followed, one participant suggested using some of these techniques with students as well, perhaps as a way of opening a one-shot session. For more about burn-out, mindfulness, and embodied practice, see Prof. Leonard’s Padlet of resources.

Presented by Jessica Wagner Webster (Baruch College)

Blog post by Alexandra Hamlett (Guttman Community College)

Jessica Wagner-Webster described her undergraduate course “Digital Traces: Memory in an Online World” and how she used active learning techniques to help students grasp archival concepts. She spoke about her syllabus and course content and the initial challenges of introducing students to the notion of an archive, as students are especially unfamiliar with the concept of a digital archive and often had not considered the lasting impact that a digital archive has on the historical record.

In her course, she used active learning techniques so that students could more directly interact with the course materials. For example, one activity had students probe questions about archiving a CD-ROM. Students analyzed the content, decided what content they would archive, and considered how to archive the materials in an ever-changing technological environment, mirroring real-world problems that digital archivists face. In another activity, students participated in a multi-week debate on the topic of police body-cams. Students were productively engaged in the debate, while simultaneously exploring the complications that technology and privacy present in the process of archiving digital materials.

Finally, Prof. Wagner-Webster employed a jigsaw reading strategy so that students would be engaged in peer-to-peer learning and teaching. Unfortunately, she found it was still a challenge to get students to complete their assigned readings, and so this active learning strategy did not go as planned. Part of the reflective process of teaching! By the end of the semester, it was clear that active learning had helped students better understand key concepts of digital archiving.

Spring Training reports – part II

Today we share the second installment of reports on the 2019 LILAC Spring Training sessions.

Wikipedia Redux: Using Wikipedia in One-Shots and Credit Courses

Presented by Monica Berger (City Tech)

Blog post by Julie Turley (Kingsborough Community College)

Professor Berger’s presentation was an opportunity to ask the audience how they have used Wikipedia in an active learning style in library instruction. Given her deep interest in Wikipedia as a pedagogical tool, she noted that Wikipedia is under-used, and when included has primarily served only as a passive “show and discuss” tool, as many librarians say they have no time for any kind of active learning in one-shots.

Dissatisfied with typical Wikipedia “show and tell,” Prof. Berger pointed out that there was much that could be done in respect to Wikipedia engagement, even in a one-shot, ranging from discussions about keyword and topic development to issues of attribution and citation. In her own classes, she noted that students are particularly fascinated with the “Talk” tab on every entry–the place where public discussion about an entry take place.

She also noted that Wikipedia is a fruitful starting point for pop cultural topics, and that Wikipedia, as an introductory site or a bridge to library resources in a one-shot, has the benefit of being instantly familiar with students, whereas they might not be with the library’s own website. During her session, Prof. Berger proposed several ideas for using Wikipedia in library instruction, including: performing a resource analysis exercise with article references using a worksheet; exploring how articles are rated in the “talk” tab and exploring the quality scale; or having students flesh out “stub” articles.

Baptism by Call Number

Presented by Paul Sager (Lehman College/Hunter College)

Blog post by Julie Turley (Kingsborough Community College)

While many library orientations “skip the stacks,” Professor Sager wants to make sure Lehman College freshman interact with Lehman College Library’s book stacks as part of orientation activities. Noting anecdotally that students don’t use the library collection of print books enough and that other info literacy activities never ask them to find a book in the library–and that nationwide, overall book circulation statistics are down–Prof. Sager thought that bringing students to the stacks might do a little, at least, to rectify this trend and expose students to valuable library resources.

Because books come up as part of OneSearch results, Prof. Sager felt a book search activity would be highly relevant. He chooses the books that students must find in advance, spacing out the call numbers throughout one designated section of the Lehman Library. Some students run into a problem when a book that is in the catalog is missing from the collection. This difficulty, however, presents a pedagogical opportunity.

“How Can We Do All This in One Session?” The Advantages of Multi-Shot Library Instruction

Presented by Derek Stadler (LaGuardia Community College)

Blog post by Sheena Philogene (Brooklyn College)

Derek Stadler described his design of multi-shot instruction, in which he incorporates three 1-hour library sessions into a First Year Seminar class, for students intending to major in the Natural Sciences. The sessions are intended to introduce various aspects of the research process and build on one another: The first session includes explanations and activities that give students a chance to think critically about their topics, ideas, and the research process as a whole. Then, the second session involves choosing relevant databases and keywords developed in the first session to find appropriate sources to satisfy students’ information needs. Finally, later in the semester, he uses the third session to show students how their newly learned research skills can extend beyond the classroom, by helping students discover more about prospective careers using research methods.

During the group discussion, Prof. Stadler said that the gaps between sessions seemed to allow students to absorb and apply the skills they learned better over time, and made it easier to build rapport with students. The group also talked about how much the multi-shot approach requires faculty buy-in and a large time investment from librarians, so it may not be as practical in cases where librarians have many sessions to teach. But when organized correctly between the librarian and professor, this method can provide the kind of point-of-need instruction that students can really benefit from.

Socratic Method

Presented by Bill Blick (Queensborough Community College)

Blog post by Sheena Philogene (Brooklyn College)

Bill Blick explained how he uses Socratic questioning during his library sessions to enhance the single session format. He opened the conversation by raising the point that students often don’t know or understand why they are taking a library session, and this makes them less receptive to the information they are given. In response, Prof. Blick has started asking students open-ended questions during library sessions. He reasons that rather than having a librarian give all the answers, Socratic questions can encourage students to do their own critical thinking, create and articulate their own ideas, and draw conclusions (find the “why”).

In the ensuing discussion, Prof. Blick acknowledged that asking students questions can be hit or miss, leading to a silent room or a discussion that is monopolized by a few students. However, when it works, this method is a good way to build a comfortable environment with students where they can feel welcome to engage with their learning and share their ideas and perspectives. Since students will need these skills throughout their academic careers, it will only help them to practice early and often.

Info Lit without Librarians?

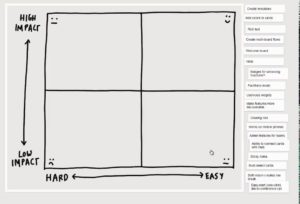

A few years ago, while attending ACRL’s Immersion Program, an instructor held up an Ease-Impact matrix, a visual tool we could use to prioritize our IL program’s efforts. As this drawing illustrates, effort is measured against impact:

In our class discussion, we decided, for example, one-shot sessions would fit in the lower-right quadrant of the matrix since they are “easy” in terms of effort, but “low” in terms of impact. One-shots are not a waste of our time, but, on their own, they are not going to make information literacy happen for our students. Yet, for most IL instruction programs, one-shots remain the primary mode of delivery. So why do we spend time promoting and delivering one-shot instruction when it has such limited impact on our students learning of IL?

Of course, I am not the only librarian to ask this question. Embedded librarianship exists precisely for this reason. But I wonder: What if the best thing librarians can do to improve students’ learning of IL is to not teach—at least, not one-shots? What if instead they redirected their efforts to focus on higher impact practices, for instance, creating PDs for faculty that focus on designing better research assignments, or, better yet, teaching faculty to teach IL?

Again, I am not the first librarian to ask this question. As early as 1997, librarians Risë Smith and Karl Mundt were arguing for a “train the trainer” approach. In their ACRL paper, “Philosophical Shift: Teach the Faculty to Teach Information Literacy,” they reason,

[F]aculty control the learning environment and are in a better position than library faculty to create situations which allow students to see information seeking as an essential part of problem-solving in a discipline. The time has come to shift our focus from the students to the faculty—to teach the faculty to teach information literacy.

Teaching faculty to teach IL might not only be a better use of librarians’ time but also a more effective mode of IL delivery. In Teaching Research Process: The Faculty Role in the Development of Skilled Student Researchers, Bill Badke argues that in order to truly invite students to the scholarly conversation, faculty must share ownership of IL instruction. Students need to understand the information habits and practices specific to their discipline, and only those in the discipline can provide them with this insider’s insight. With only librarians leading the IL charge, students learn, at best, how to imitate the scholarly conversation. They don’t learn how to participate in it.

Badke’s argument resonates with my own experience as an undergraduate. As a double-major in English and philosophy, my coursework drilled the mechanics of academic writing: thesis, evidence, citation. I worked hard and was an “A” student. But I was also a first-generation college student, so I had little understanding of scholarly communication or how it works. I studied hard because I wanted to learn, and I wanted A’s, and I wanted my teachers’ approval. The learning, the grade, and the approval were all ends in themselves. It never occurred to me to question why my teachers asked me to write 10-15 page research papers in the first place.

Then, toward the end of my senior year, my philosophy professor suggested I submit one of my papers to an undergraduate research journal. “So you can I could get a ‘publication’ on your application if you decide to go to grad school,” she said. I was flattered but also confused by her suggestion. I thought, people read newspapers and magazines, not philosophy journals: “Why would I want to publish in a journal no one reads?”

In other words, I had learned how to “imitate” scholarly discourse very well. But, with limited, superficial awareness of the philosophical discourse, I wasn’t really participating in it.

Reflecting on all of these experiences has led me to the conclusion that I can serve my students best by being selective about when and what I teach. After ten years of teaching IL, I am tired of requests for database instruction. Especially in this “Misinformation Age,” I’d much rather teach students about information types and how authority is created so that they can better evaluate the information they encounter every day. Besides, faculty, as disciplinary experts, should be able to teach students how to use the databases appropriate to their disciplines. And if they can’t, we really should be helping them.

Of course, it’s easy for me to say. My school’s founding documents specify that information literacy skills ought to be built in the context of students’ courses (p. 25). Also, considering that they are employed at a community college, most of our disciplinary faculty embrace their teaching role and so are receptive to teaching IL.

It also doesn’t hurt that my colleague, Alexandra Hamlett, and I have created a “toolkit” of IL lessons and assignments for faculty to use in their instruction. It’s a lot easier to convince faculty to embrace their IL teaching role when you can make their class preparation and teaching easier for them.

We published the toolkit in early 2017 after mapping IL outcomes to the first-year curriculum (we are still working on program-level mapping for our five majors). Specifically, we reviewed syllabi from the required first-year curriculum and looked for areas (course level outcomes or assignments) where IL was either identified or presumed. In this way, we could create IL lessons and handouts that would complement the first year curriculum.

The lessons themselves are framed on the ACRL Threshold Concepts and so attempt to contextualize IL skills so that students can see how IL relates to the “big picture,” that is, to their own lives, so that they can better transfer their knowledge to different settings (other classes, jobs, etc.). We promote the toolkit to faculty during weekly House Meetings (similar to department meetings), on faculty listservs before the start of each semester, and through standalone PDs for full and part-time faculty. We have also experimented, through grant funding, with offering faculty a small stipend for participating in a “how to” PD on IL instruction and revising their course syllabus to better embed IL into their instruction.

But other librarians, feeling strapped for ideas or time to prepare new lessons, could easily use this toolkit for their instruction, too. Check it out at: https://guttman-cuny.libguides.com/facultytoolkit

In addition to our own, I am also a fan of the Library 101 Toolkit, created by librarians at Duke University, and this toolkit of lessons created by librarians at the University of Northern Colorado. Built upon a critical pedagogy framework, these lessons emphasize student voice, personal narrative, and collaborative learning.

I do not think that teaching faculty will ever replace librarians’ IL expertise. I do not worry that by teaching faculty to teach IL I am somehow putting myself out of a job. Rather, I feel like I am better managing my instruction responsibilities. By being selective about when and what I teach, by pushing back (a little!), I now have more time to dedicate to one-on-one research consultations with students, faculty PDs, and other high-impact practices.

Spring Training reports – part I

After a rich experience at the 2019 LILAC Spring Training on 7, LILAC committee members and attendees are reporting back on the sessions they experienced that day. Today we share the first installment of those reports.

Using Instructional Scaffolding to Teach Scholarly and Popular Sources

Presented by Mark Aaron Polger (College of Staten Island)

Blog post by Yasmin Sokkar Harker (CUNY Law School)

Mark Aaron Polger started by defining and giving background on instructional scaffolding and how it has been used. He also explained how instructional scaffolding sometimes happens organically (and gave examples of scaffolding activities that we may already be doing, such as concept maps or supplemental Libguides).

He described a case study in which he compared two sections of LIB 102, one scaffolded and one control group, explaining how he created and worked with each of the groups. The scaffolded groups were student-led, with students evaluating various sources and generating discussion. The non-scaffolded groups were teacher-led and the teacher described characteristics of different kinds of sources. He discussed the differences between the groups, and the benefits of scaffolding, which include a deeper understanding of both scholarly and popular sources. Prof. Polger’s presentation was fascinating and generated much discussion on student learning.

All in Kahoot’s: Tools for Active Learning and Assessment

Presented by Jeffrey Delgado (Kingsborough Community College)

Blog post by Robin Brown (Borough of Manhattan Community College)

Professor Delgado advocated for Kahoot, an effective platform for designing games to enhance instruction. He reminded us that students are not always paying attention during one-shot instruction sessions, and that following up with a quiz or survey in an attractive format is a great way to reinforce instruction. Professor Delgado showed us how easy it is to offer a quiz, by offering us one. It’s relatively simple to use a phone, tablet or laptop to go to Kahoot and put in a pin number. This was an effective presentation of a tool that easy to try (basic registration is free).

Extending and Improving Your One-Shot with Google Forms

Presented by Neera Mohess (Queensborough Community College)

Blog post by Robin Brown (Borough of Manhattan Community College)

Professor Mohess showed how she is using a Google Form to pre-test and post-test library instruction classes. A link to a specific form is sent to the professor before the library instruction session, with a request that the professor forward it to the students. Professor Mohess then uses the students’ responses to respond to specific concerns during class. Just before the project is due, she sends a second survey for the professor to distribute to the class, and later sends a summary of the follow-up questions. This is an interesting way to extend the library instruction classroom.

Scalability

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about scalability. This is not a new idea for me, but it has certainly been popping up more in my mind and sticking around longer. Maybe it’s because every year the middle-of-March madness creeps up on me and nearly knocks me over–how is it, really, that I can have forgotten how frantic I’d be? So many email exchanges with instructors; so many reference shift swaps; so many last minute changes; so many lesson preps; so many worksheets! Yet it’s the same every semester: in the beginning, I’m doing systematic outreach to all the full-time and adjunct faculty teaching in my liaison areas–I want them to remember that the library exists, right? And that we’re here to support teaching and learning on campus? By about six weeks into the semester I’m almost secretly hoping they’ll forget my name because I fear I’ve already bitten off more than I can chew.

I haven’t yet figured out how to solve this dilemma, but I started poking around a little to learn more. Lorelei Rutledge and Sarah LeMire include a discussion about scalable models in a broader article addressing new ways to think about information literacy on campus (Broadening Boundaries: Opportunities for Information Literacy Instruction inside and outside the Classroom). For Rutledge and LeMire, it seems the main crux of the issue is about finding new and creative ways to infuse information literacy instruction into students’ academic lives, rather than strictly about relieving scheduling issues among teaching librarians. You see, the problem isn’t just that there isn’t enough time in the world to teach workshops for all the instructors who might want them, but also that our students would benefit from a greater degree of information literacy support, in general. Rutledge and LeMire call our attention to what they call “opportunities for microteaching on campus,” for instance by including “snippets of information literacy instruction” in large-scale campus outreach events, or becoming a mentor for student organizations or committees. They suggest teaming up with potential advocates among stakeholders on campus who could act as ambassadors and library boosters, working hand-in-hand with campus writing centers to prepare writing tutors to help their peers with research and information literacy challenges, working with the Center for Teaching and Learning on campus to help with faculty PD, and developing train-the-trainer programs to support instructors who might be interested in teaching their students information literacy skills and knowledge.

I’m really attracted to the latter idea: finding a way to better empower instructional faculty in the information literacy crusade–the old “turnkey” approach. One of the first formal train-the-trainer initiatives I became aware of is The University of Texas at Austin’s Information Literacy Toolkit (although the Texas toolkit may not have been the first such resource, as the IL Toolkit at the University of Minnesota has been around since at least the early 2000s; see Butler & Veldof, 2002). UTA’s Toolkit LibGuide provides openly licensed resources for faculty, including customizable assignments linked to related guides and tutorials, complete with instructions and example student work, in-class assessment activities, and narratives about sample courses and their implementation of IL assignments and assessments. The Toolkit also serves as a channel for informing instructors about how they can reach out for a consultation with a librarian, request a custom-designed research assignment for their students, or schedule a workshop with a librarian.

In March of 2018, Marielle McNeal from North Park University in Chicago facilitated a webinar on the train-the-trainer model for an Illinois consortium of academic and research libraries. What struck me as I read through McNeal’s outline was the idea that we might be missing something in our efforts to help our instructional colleagues if we focus primarily on trying to teach them better ways to design assignments or courses, and neglect some of the barriers faculty face when it comes to teaching information literacy. As she points out, our colleagues may not fully understand all the factors impacting students’ information literacy challenges, and are most likely not well versed in major IL concepts or familiar with best practices for teaching IL. Sometimes I simply lose sight of the fact that the faculty with whom I collaborate are content experts in their own disciplines, and not necessarily in mine.

There are a lot of fantastic ideas out there! But it’s clear that any scalability initiative has to be customized to the institutional and library context. When I read about building a network of boosters or coordinating with the writing center or launching an online toolkit, I have to wonder how taking all that on could possibly relieve the pressure I’m feeling right now. Obviously, to set up any kind of scalability initiative will take a concerted investment of time and attention and it’s probably not something to dive into without some strategic and collaborative thinking. This year, as I emerge from my mid-March frenzy, I plan to keep the issue on my radar. Maybe I can break the cycle. In any case, I’d love to hear about any experiences you’ve had working to address the scalability issue.

Gaming for Info Lit Flow

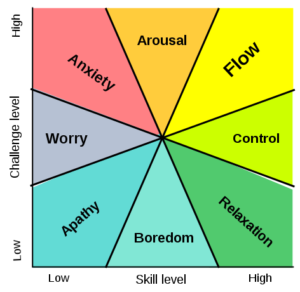

A few years ago Michael Waldman at Baruch Library was kind enough to recommend what he described as the least intimidating marathon training book, The Non-Runner’s Marathon Trainer, which introduced me to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow, as applied to long distance running. I learned that flow, an intense state when you’re fully engrossed in an activity, is usually attained when you challenge yourself to go beyond your skill level, but not so much that you’re intimidated (see graph).

Flow makes me feel radiant! So I look for opportunities to achieve flow whenever I can, whether it’s in my personal or professional life, including my teaching. In fact, I’ve noticed that some of the most memorable experiences I’ve ever had as a student were when I experienced flow in a fun and immersive environment through a creative assignment or a game of some sort – as part of a junior high school moot court defense team or as an adult learner when our teacher tested our class’s knowledge of a unit (on some rather dry material: intergovernmental legal documents) using a Jeopardy-style game complete with prizes! So, I have long believed in the power of gaming (table-top games, role-playing games, video games) for educational purposes.

And while I’m by no means immersed in the gaming world, I’m an advocate. A few years back, I was at a meeting where a student was demonstrating an online role-playing history game for a room of educators. I overheard one professor at my table privately question the educational merit of playing the game, which seemed to her to be a matter of mindless clicking to advance to another screen, with no intellectual rigor behind it. Sometimes when gaming is used in pedagogy, it’s frowned upon because there is an impression that it’s superficial or gimmicky. So I raised my hand and asked the student to explain whether players would need to have a foundation – to draw from a knowledge base – in order to make decisions about how to proceed in the game. He agreed that they did and explained how. The educator may not have been converted or even convinced, but I felt that gaming’s merit scored some points that day: games can enhance and foster learning by providing an engaging and relatable environment in which students can reflect on subject matter. And yes, games do provide opportunities for thoughtful, critical thinking.

In the fall of 2018, I used a mock trial role playing activity in my 3-credit freshman history course on the Conquest of Latin America. I hand selected student groups to represent five different defendants (Christopher Columbus, Columbus’s Men, The Crown, the Taínos, and the System of Empire) against the charge of the genocide of the Taíno population. What I thought would be a three-session activity turned into a four session one, and could have easily gone on for five or six. It was a remarkable experience for me. Some of the quiet students became very vocal during the mock trial and those who were typically talkative in class became even more impassioned. After one defense team stated their case, a student in the audience questioned them past the allotted class time. Some students with scheduling conflicts left, but about half the class intently and respectfully stayed behind until I had to cut the debate short because another class was scheduled to use our room. These markers of engagement made me feel that we had achieved “flow.”

One of the most enthusiastic students left an impression on me by telling me that she didn’t know whether I just had a keen eye for knowing which students would click, but she was very surprised that she wound up becoming fast friends with her teammates. While I’d like to take the credit, it was actually a lucky confluence: all the students were also registered in a second writing course, making them a learning community, so these friendships would have developed sooner or later as a matter of course. However, one thing is certain: this type of group work and role-playing game helped cement some of those relationships. So, I think another added benefit of gaming of any kind is that it can encourage dialogue and camaraderie.

Beyond all the intelligent, nuanced, incisive arguments and reasoning that went on during the course of those two weeks, I could tell that the students were also having fun. Students owned their personas and took pride in the arguments they would present. They created professional looking PowerPoints, used music, asked for audience participation, and they dressed up as King Ferdinand, Queen Isabella, and even the Pope! Playing makes learning more fun at any age and gaming is a great way to foster flow in our students’ academic lives as well as our own.

I was pleased, then, when I first came to CUNY and learned about The CUNY Games Network. I attended this year’s CUNY Games Conference 5.0 after a hiatus of a few years. It was a neat departure from the previous ones I’d attended, where the main presentation format was a panel or talk (the organizers had opted for this more participatory format before, but it was my first experience with it). I attended the “Redesign: Modifying Tabletop Games for Instruction” workshop run by Joe Bisz and Carolyn Stallard, where we played the games “Apples to Apples” and “Snake Oil” and later discussed their mechanics and how we could use these to enhance our own instruction. During our discussion, we brainstormed a possible modified version of “Snake Oil” for a history course: the cards could be different historical figures studied during the semester and the dealt cards could all include other historical figures or resources that could help the historical figure advance in the game. We did not work out the specifics, but it would be a great game to play at the end of each unit to help students reinforce their knowledge and help them become more conversant and confident with the subject matter.

In Bisz’s second workshop, we played his What’s Your Game Plan? A Game for Growing Ideas into Games, an actual table-top brainstorming card game available for purchase. We were asked to choose a lesson (normally, you would choose a lesson card in the course of the game) and we were then asked to create a game for this lesson using pre-selected cards that required us to use a specific game (Checkers, Jeopardy, Scrabble, etc.), mechanic (movement/sport, jumping, role play, etc.), and action (investigating, bluffing, trading, etc.). Each group at that workshop created the basic parameters of a game for different lessons in various disciplines.

My flow-like experience with the history course students and the brainstorming at these practical workshops renewed my interest in incorporating gaming into library instruction. If you feel that you can’t possibly incorporate a game into your library instruction because you don’t have the luxury of teaching a 3-credit class, you’ll be happy to note that librarians have shown that this is totally possible in a one-shot library class. City Tech Chief Librarian Maura Smale modified Bisz’s brainstorming game and Tiltfactor’s Grow a Game to come up with the open access Game On for Information Literacy, which has been used by CUNY librarians to create a game that could be used in one-shot classes learning MLA citation style. CUNY librarians have also created a rubric for different information literacy games that can help us as we create games of our own. Do you have or know of an info lit game that can be incorporated into a one-shot class that you’d like to share? Let me know (ddominguez@ccny.cuny.edu) and if there is enough interest, I can put together a gaming for into lit flow toolkit to share!

Transferring skills from arts ed to info lit

The last job I held before becoming a librarian was as a facilitator of arts programs, working 11 years for ArtsConnection, a non-profit that brought professional visual and performing (music, dance, theater) artists into public schools pre-K-12 throughout the five boroughs of NYC.

Each time I’ve changed careers, I’ve tried to carry over whatever I managed to learn in one field to the next. Here are four aspects of teaching that I came to value in arts education that have proved useful guideposts for me as a teaching librarian at Hostos Community College. I hope they may be of some use to other teaching librarians as well.

(1) Collaborative teaching partnerships

Then: Although we provided a diverse range of in- and after-school instruction, the most common project was a 10-session residency of workshops held once a week, in class, with the classroom teacher present as the artist taught.

Classroom teachers often had limited or incorrect assumptions about what our teaching artists, as visiting instructors, could offer their students. They didn’t want their time wasted.

Given our brief stays in each school, it made a huge difference when teachers saw the worth of our programs. An engaged teacher helped students make connections between learning in the arts workshop and learning in the classroom, even if there was not a direct curricular connection, and their very engagement gave students the message that the work in the arts was an important part of the school day.

Deciding to be an at least watchful or even enthusiastic presence during the workshop also gave classroom teachers an opportunity to learn more about their own students. Teachers often told us how their perception of a given student’s ability (to concentrate, take risks, create, inspire others, work toward a goal) was transformed by watching the student learn in the arts.

Planning and goals

The first step to getting teacher buy-in was our planning meetings. The classroom teachers and the teaching artist often started out with different vocabularies regarding student learning, and my job as facilitator was neither to force the artist into edu-speak nor to force the classroom teacher into artist-speak, but to help bridge a common understanding and shared set of goals.

Some (certainly not all) teachers, under tremendous pressure to raise English and math test scores, were reluctant to “give up time” and assumed that the arts work would at most give students a chance to blow off steam and have fun. Planning meetings allowed us to show how learning in the arts would help students build both particular skills within the art form and broader skills such as problem-solving, empathy, collaboration with peers, public expression, and creative discovery.

It’s not that teachers didn’t want those things, but they weren’t (usually) artists, and we couldn’t assume that they would see or articulate such goals spontaneously before the workshops, or see exactly how the arts could bring such learning to their students.

Laying the abstract groundwork of goals was always important, but the real buy-in came when teachers saw their students learning in the moment. When teachers saw students engaged with something worthwhile, they were won over to working with the teaching artist as partners.

Now: Although academic librarians provide a diverse range of instruction, through workshops, reference interactions, consulations, online guides, and semester-long courses, our most common method of instruction is the one-shot workshop to support a course’s research assigment.

Professors in the disciplines often have limited or incorrect assumptions about what we librarians, as visiting instructors, can offer their students. They don’t want their time wasted.

I’ve found that professors who aren’t just grading papers in the back but actively observing and engaging in the research workshops (such as circulating as I do as students work in small groups or on their own) help students make connections between what they’re learning in the workshop and their classroom learning. Professors’ engagement sends the message that the library workshop is an important part of the course.

I have also seen observant professors change their understanding—not as much about their students’ abilities, but about the reality of how students grapple with their research assignment, or still have questions that the professor thought had been made clear in class. These observations help us in our discussions as we evolve our teaching partnership in subsequent semesters.

Planning and goals

In initial planning conversations, we often start with different perspectives and ways to assess student learning. Some professors may be reluctant to “give up time” and assume that all a library workshop could do is introduce students to the existence of EBSCO. Well-meaning professors who start conversations with a request to “teach them how to cite” or “how to use the databases” or even “how to research” as if that were a 75-minute task, remind me of those K-12 teachers who hoped that dance might somehow improve math scores. What they’re really saying is: please do something with my class that will be of use to them, and here’s what I assume that help might look like.

Just as we librarians shouldn’t always take a student’s opening query at a reference desk at face value, but instead use a patient, listening, probing reference interview to see what it is they really want and what might help them more, I believe that these opening queries from professors offer us a similar opportunity to start a real planning dialogue.

Communicating goals in advance helps lay the groundwork. As teaching librarians, we know it’s not just being able to navigate a proprietary interface that counts, it’s a myriad of understandings, whether captured by the abstract intellectual concepts of the Framework or the liberating perspectives offered by critical information literacy; it’s also learning concrete skills and habits such as developing a focused inquiry as a more propulsive start to research in place of an overly broad topic, or distinguishing between kinds of available sources and learning how to use them strategically instead of haphazardly; it’s acquiring habits such as browsing the stacks because it turns out that books are organized by subject, or questioning every website they come across by asking, okay, who wrote that, what’s their agenda, and why should I believe them?

It’s not that professors don’t want these things, but they often aren’t thinking about all the particular elements of research that students confront. We can’t assume that most would articulate such goals spontaneously before the workshops, or see exactly how engaging in a research workshop could bring such learning to their students.

The real buy-in comes when professors see their students learning in action. The more they see students engaged with something worthwhile, the more they are won over to working with us librarians as partners.

(2) Learning through authentic experiences in the discipline & student voice

Then: I learned that students’ being active in class is necessary but not sufficient for learning. When students had an authentic experience in the arts, going through real steps of experimentation, making choices, stepping back to assess, revising, and innovating further—rather than following pre-ordained steps to creating a product–their learning was much more meaningful. Those residencies that most allowed for students’ original vision to guide the project and for their voices to shine through were inevitably more powerful than a slick, more teacher-directed project.

Now: What are the authentic experiences in research? If we show students the library’s discovery layer or a database and indicate how to click a couple filters, but the student just prints out the first five articles whose titles happen to echo their keywords, we know that’s not engagement in an authentic research process.

As Anne Leonard said here in an earlier blog post, the complex and iterative process of research is something learned over time, and often students are still growing out of a conception of “research” as a quick looking up of set answers to imposed questions. Authentic research processes of defining their own inquiry, searching, selecting, reading, discovering new ideas and developing new questions, reframing their inquiry, and so on, are new to many of them.

The extent to which we can influence the structure of a research assignment varies wildly and we of course can’t force students to engage deeply. I’m also aware that our students at Hostos are often juggling work, family, and other obligations, and understand that not every single research project will pull in 100% of their effort.

That said, whether in workshops, at the reference desk, or in one-on-one consultations, we can ask them to do more than follow our examples of where to click on a screen, and can directly address the progressive nature of research and the idea of searching as strategic exploration.

Helping students follow their own paths through their research also means helping them understand good places to start, and showing them how to strategize their search, for instance knowing when they would be helped by first reading background texts to be able to confidently engage with more scholarly sources. We can to the best extent possible help students take as much ownership as a given assignment will allow.

(3) Big picture learning while planning the particulars

Then: The teaching artists we worked with were required to write out their plans for a residency, including learning goals. Some viewed this process as paperwork or as restrictive, but many came to value the reflection demanded by posing the questions: what do I want students to know and be able to do after this lesson? What are the larger understandings in the art form that they will start to build?

Writing out a lesson plan also helped artists determine the scope of what they could do, given the limited number of minutes and days in a residency.

Now: Although I don’t start out with the Framework as a base for workshops, I find that its larger understandings often slide organically into lessons. Here are just a few examples:

- Media literacy workshops offer obvious opportunities to address the idea of authority as constructed and contextual, although I also touch on this idea in workshops in which students engage with Library of Congress call numbers, noting that although it’s useful for students to be able to navigate this system, it was created by a specific institution in a specific historical context and certainly has flaws that we can critique.

- Any mention of needing to sign in with a CUNY ID in order to get access to database articles off-campus is an opportunity to show that information has value and that access is limited because of the way that publishers make money and that educational institutions comply.

- When students say they already know exactly what their paper will say before having read any “sources to cite”, we can raise the idea of research as inquiry and of discovering new ideas. Two informal writing prompts I use in many workshops are “what are some things you already know about your research topic?” and “what do you want to find out that you don’t know yet?” These are simple questions, but kick off discussion in which we address the idea that the research process is not just about looking up people who reiterate what you already think.

- Often in workshops, I’ll address the fact that they will encounter equally qualified and credible writers who sharply disagree on a subject, and that part of the students’ work as researchers and writers is to grapple with those arguments—understanding that scholarship is conversation, not just a canon of obvious, universally accepted, and unchanging facts.

Writing out lesson plans also helps me see what I can accomplish in one workshop. Sometimes I have heard librarians say they don’t have time for the bigger picture, but in writing down my exact plans, I have found not just things that need to be cut (I think a common librarian urge is to try to say too much), but also natural places for just raising questions and planting seeds; a lengthy exercise or discussion is not always necessary to integrate bigger-picture ideas.

(4) The importance of a teacher’s energy

Then: Although I had known this from many years of being a student, observing dozens of teaching artists each year and clocking literally thousands of hours of observation over the course of a decade showed me over and over that the energy you put out as an instructor is the energy you get back.

Now: I have seen some librarians and some professors who whether from shyness, self-consciousness, or perhaps a feeling that it is more authentic, teach with the same voice they might use in a one-on-one conversation, or in a small group meeting. In these cases, the energy and attention of students tend to untether and drift out of the room.

As for nerves, something I learned previous to my last job was that jumping in with gusto burns off much of the nervous energy, and the attentive response you get in return kills off the rest. As for the desire to remain authentic, I have found that after a while, your heightened “teacher voice” is just another equally authentic version of yourself.

Although I’m certainly not as skilled as a professional actor, I channel as best I can the kind of enthusiasm, responsiveness, and direct engagement that I loved in our most effective theater teaching artists, and I usually get great energy back from students. If I’m tired or if it’s the third workshop in a day, I can feel my lower level of energy and a corresponding drop in the room, so I know it’s not just the lesson plan that makes a difference.

Although my lesson plans focus on what I want students to learn and be able to do, right before every workshop I stop and ask myself (knowing I may be distracted or stressed with other worries), “How do you want the students to feel?”

This question forces me to remember that I want students to feel happy to be there, welcomed, excited about learning, and confident that they will be able to take charge of their research–and remembering that helps me to walk into the room with energy that reflects those aspirations.

The Power of PowerPoint

Alright, maybe it is not that powerful, but at least, useful.

In my college days, professors’ lectures were mostly verbal and sometimes aided by a blackboard. The professor would either talk my head off throughout the whole lecture non-stop making me take notes busily in the fear that I might otherwise miss some important things, or in a better situation, write some key points on the blackboard with a chalk but I, occasionally if not often, had to do a guess work due to an individualized handwriting. Sometimes, the professor might use a slide projector making things a little better, but I still struggled with the handwriting on the slides. I never had a class that featured in PowerPoint presentation because that was in the last century, a long time ago before PowerPoint came into common use in classroom teaching. Thanks to technology that makes teaching both verbal and visual.

My first attempt to use PowerPoint was in 2002 when I was engaged in a summer teaching exchange program between CUNY and Shanghai University in China. The two courses that I taught, Introduction to Information Sources & Services and Using the Internet for Research, had two hundred students in each. Class size was incredibly large compared with the American’s (we have an average class size of 25 at York), partly because the students were interested in the course contents (and partly … hey, it’s a populous country.) The classes would be held in a large lecture-hall and I would have to use a microphone to deliver lectures. All seemed okay except it might be difficult for students sitting in the back to take notes from distance. Then I discovered that the room was equipped with a computer and a projector for the lecturer. I decided to try to use PowerPoint instead of using a traditional blackboard. However, I was a novice user and knew little about the software. Fortunately, my teaching assistants, assigned by the university, were tech savvy. They taught me the basics and showed me some useful tips. (Off the topic: they also helped me “climb over the wall” because some databases and websites were blocked by the so-called “Great Wall”, a government-backed internet filtering system, but I needed to use them for classroom demonstrations.) All lectures went smoothly and the university was pleased to see the students learning outcomes. Since then I have used PowerPoint frequently.

It must be stated that I am no expert in the full spectrum of PowerPoint universe but a happy user of it. In my practice I enjoy the following benefits from using PowerPoint to teach one-shot library workshops.

It is visual

In addition to our talking, students can enjoy the graphs, diagrams, tables, images, and photos that are visually descriptive in effective ways. Thus, the students can get a better understanding of our points.

It is multimedia

We may use Animations, Transitions, Audio and Video files to enhance the presentation and to enrich user experience.

It has multiple usages

We can save the PPT file as PDF and make it handouts for students to use during the session and/or for future reference.

It makes it easier for students to take notes

Students never need to guess what’s on the projected screen since the text is typed.

It is more than a local file

We can hyperlink reference databases and websites to introduce sources from our library’s subscribed databases and on the Internet, and access relevant information with a click of the mouse.

I also recommend the following tips.

- Use large fonts for both heading and text for easy reading.

- Use timed presentation if you are good at time management.

- Use click-controlled presentation if you want to have more control over slides.

- Don’t use the background color that is too similar to the text color.

- Don’t use too much text on a single slide.

Attached here is a sample PPT file which I use for orientation workshops.