Home » General (Page 3)

Category Archives: General

Searching as strategic exploration: towards an embodied information literacy

As instruction librarians, we know that the iterative, sometimes nonlinear, search process is an expert searcher’s ability; it comes only with practice and through experience. Yet novice researchers – undergraduate students – may not yet have had this experience and practice. Consider how students could embody information literacy. Students embark on metaphorical journeys in the search for more, and better, information on a topic. In the search process, students circle back to their keywords, explore new disciplinary frontiers, cross thresholds, and reiterate their search strategies to become ever more confident and competent in a new domain of knowledge. Walking, journey, and travel metaphors can be found everywhere in higher education. CUNY’s general education framework is called Pathways. We speak of the pursuit of knowledge, of a student’s path to graduation, and of degree mapping.

What if we put metaphors aside and documented (mapped) the progress of searching as strategic exploration? Consider students’ lived experience. They all bring with them embodied knowledge that is located more in the realm of intuition and insight. What if we helped students discover their embodied knowledge through reflecting on this iterative process of searching? In your next one-shot, consider asking them to uncover knowledge they already possess by posing one-minute paper prompts such as, “What was your a-ha moment (or challenging moment) in today’s class, and why?” or “How can you apply what you learned in future research?” This generates a map or milestone in the student’s journey to information literacy.

While I have found that a reflective and creative approach to the frame searching as strategic exploration valuable in my information literacy and library instruction work, I recognize that it is not the only frame. It was not even the frame that initially resonated with me. I’ve come to realize that there is great value in doing a deep dive, or taking a long walk, with one frame. Whatever frame you choose, make friends with it. Consider yourself in a long-term (though perhaps not exclusive) relationship with it. You just may find yourself drawing on your deep knowledge and familiarity with that frame extemporaneously, particularly in those instruction sessions that do not go according to the lesson plan.

Thoughts on reflection prompts and questions you’ve tried, or would like to? Leave a comment below!

A few suggestions for further reading:

“Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), 9 Feb. 2015.

Kerka, Sandra. “Somatic/Embodied Learning and Adult Education.” Trends and Issues Alert. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, 2002.

Spatz, Ben. “Embodied Research: A Methodology.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 2017, pp. 1–31.

What does a librarian teach?

- Authority as Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

As you can see from this list, information literacy has been recast as being about ideas. How is authority defined? How do we think about information? It takes real work to integrate these ideas into the day-to-day work of a growing one shot program. I appreciate that it gives a target to shoot at.

A teaching librarian fails at summer vacation

It’s August and I’ve been reflecting on whether I’m making the most of the quiet summer months in our academic library. I’ll confess that I approach summer “break” with an aspirational attitude similar to the one that sparks New Year’s resolutions. And yet, come August, I annually feel panic about whether or not I’ve made the most of my summer. As the academic year ends, I begin to create my mental list of summer projects, things like catching up on reading, cleaning off my desk, planning for the coming year, and working on becoming a better teaching librarian, all before the new semester starts. In past summers, I’ve really emphasized that last one — become a better teaching librarian — leading to unnecessary pressure, and unexpected results.

In May 2017, for example, I attended LOEX for the first time. I returned to my library buzzing with new ideas to improve my practice. When summer rolled around, I decided to turn those ideas into a single project: developing a lesson plan around strategic searching, which I am frequently called on to teach. This lesson would be different from those lessons that I rush to put together during the semester. With this lesson, I would be more deliberate in my teaching. A pre-made lesson would also streamline my practice for a busy fall. Finally, with the extra time, I could focus on the areas where I had seen students struggle in the past year.

I optimistically estimated that the resulting lesson, a script for me and a two-page worksheet for the students, could be taught in 75 minutes. Ha! I never found out as I was too daunted to try it. Initially, I told myself that the lesson wasn’t a good fit for the particular classes I was teaching. Revisiting the lesson to write this post, I see now that it was much too complex and not at all appropriate for a one-shot. More likely these exercises would have taken at least two class sessions to do well. Having put in hours of work with little to show for it, my big summer project felt like a colossal failure.

There is a happy ending, though, as I’ve learned several valuable lessons from last summer’s experiences. First, summer is not the best time (for me, at least) to develop my teaching because I’m not actually working with students. My lesson plan was not coming from an authentic place; it was developed for imaginary, idealized students. However, revisiting the lesson, I now realize that I have incorporated some elements of it into the lessons that I developed during the academic year. The thinking was useful, even if I couldn’t use the original product. Finally, I’ve changed how I think about summer. This year, I have spent my time catching up on reading and doing some much-needed writing. I’ll save the actual lesson plans for the semester, when the ideas of the students are much closer.

What New Things Can I Do?: The Roles and Strengths of Teaching Librarians (ACRL, 2017)

Taking a bit of time this summer to catch up on my professional reading, particularly as it relates to instruction, I once again happened across The Roles and Strengths of Teaching Librarians (approved by the ACRL Board of Directors, April 28, 2017). I had observed the advent of this reimagining of the 2007 Standards for Proficiencies for Instruction Librarians and Coordinators a little more than a year previously, while in the throes of an end-of-semester blur, but at the time I had filed it away as something to come back to when I could afford it closer attention.

The document describes shifts in thinking about teaching in libraries, precipitated in part by the shift from Standards to Framework in thinking about what and how we teach. Our profession has seen a rapid evolution of skills and responsibilities, and there was a desire to articulate a perspective inclusive of the broader range of work that is being done, the variety of institutional contexts, and the different ways we practice teaching-related work in libraries across our careers. The new document provides a conceptual model of seven roles, and a description of the strengths a librarian might need in order to thrive in each of those roles: advocate, coordinator, instructional designer, lifelong learner, leader, teacher, and teaching partner. The document stresses that these roles can and often do overlap, that individual librarians may find they identify with some of these roles more strongly than with others, and that it is not necessary (and may even be a little crazy to think) that any one librarian would or should possess all of them.

The document suggests certain benefits to this re-conceptualization. If you’ve ever found it challenging to describe the sometimes unique and somewhat abstract teaching work you do, this new model may help you name, describe, and situate your practice relative to the other work of the academic enterprise. Four to eight strengths are listed relative to each of the seven roles. For example, as a teaching partner, you may “[bring an] information literacy perspective and expertise to the partnership,” and as a lifelong learner, “[actively participate] in discussions on teaching and learning with colleagues online and in other forums.” If one goal is to be able to think about and talk about the myriad ways we support learning in libraries, this tool has a lot of flexibility. However, the idea that struck me most in reviewing the document is the notion that, with a reinvigorated and perhaps clearer conceptualization of the teaching-centered practice of academic librarians, we might ask ourselves the question: what new things can I do? As acknowledged by the framers, this document is both reflective of actual practice and aspirational.

As a bonus, I also found myself interested by the process of the revision task force – how they actually arrived at the conceptual model, roles, and strengths. So I encourage you to take a look, if you haven’t already. There’re still a few weeks left before the end of summer and the beginning of chaos.

4 Reasons Why You Should Keep a Reflective Teaching Journal

Back in January, I was casting about for some instructional inspiration. What could I do, what could I try to improve my teaching in the upcoming semester? A light bulb went off when I suddenly remembered Betsy Tompkins’ (2009) excellent article on reflective journals. She suggests that the systematic practice of recording teaching processes, decisions and behaviors may be “a source of inspiration and professional development” (Tompkins, 2009, p. 232) to academic librarians. Motivated by her example, I experimented with a reflective teaching journal during the Spring 2018 semester and was delighted with the results. Below are my four best reasons why you might consider keeping one yourself.

- Cheap and easy

No need to register for another expensive webinar or workshop. This professional development opportunity will cost you nothing more than a bit of time and effort. To get started, all I did was set up a journal entry template in Word, modifying Tompkins’ (2009) form to include sections on materials, assessment and future planning. Over the course of 15 weeks, I used this template to create entries on 25 one-shot sessions. I’ve included my template in this post as well as a sample entry prepared for a BU401 Elements of Marketing class.

Typically, I would fill in a template through the “Summative Assessment” section before the class meeting; this act of writing actually enhanced my lesson planning. Then I tried very hard to complete the “Post Class Reflections” and “Link to Future Planning” sections immediately following the class. The latter didn’t always happen, but I found I generated much better insights when I journaled right away.

- Good data

A teaching journal can help remind you what to do different and better the next time around. Recently, I was asked to teach a summer section of Elements of Marketing with two days’ notice. I pulled out the Spring 2018 BU401 journal entry below and was immediately reminded to update my materials with the new textbook title and with a U.S. Census citation demonstration.

I am hopeful that my journal notes will also inform conversations this fall with returning classroom faculty. Rather than passively accepting incoming instructional requests, I now feel equipped to initiate specific recommendations and suggestions. Two possible examples include:

- “Follow up with (professor’s name) re books as sources conversation. If in fact he does link book use to better papers, perhaps we can devise an assignment whereby students locate and engage with one book related to “Exit West” themes.”

- “It was progress that she included a graded assignment related to the library session. But maybe going forward, we could push beyond finding the article and add on reading/understanding the article. I take responsibility for that, and will be more assertive going forward.”

- How am I doing?

A lot of my entries are pretty basic, like “I was flat today” or “This lesson plan has too much content” or “Consider eliminating the research question video.” But in February I wrote up an experience which I am still thinking about. A student stopped me after class and said: Excuse me, professor. I hope you don’t mind me asking. How do you think you did today? I was startled and amazed by his question. When I asked if he wanted to give me any feedback, he shared: You are too comprehensive. Students are not robots. Just say – there’s information out there if you want it. And you know what, he is right! I sometimes worry so much about clarity and connecting the dots, that I often do not leave space for trust and discovery. Journaling helped me to process this truth and has helped kept this experience front and center all semester.

- Teaching artifact

An academic librarian can use a reflective journal to improve her teaching. She can also use it as an artifact of her instructional efforts. I plan to print all my Spring 2018 entries and organize them into a notebook, which I will then deposit into my Queensborough personnel file. That journal is a detailed record of my teaching activity; and while it may not hold the same currency within CUNY as student evaluations and classroom observations, it does provide authentic evidence of my commitment to teaching and learning.

Reflective Teaching Journal – Template

Reflective Teaching Journal – Sample

LILAC Spring Training RSVP

LILAC Spring Training: Up Your Game!

Practical Innovations Beyond Traditional Information Literacy

Friday, June 8th, 2018 | 12:30 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

CUNY Central | 205 East 42nd Street Room 818

The LILAC Spring Training is an afternoon filled with presentation pitches, a facilitated group activity, and more. Presentations, discussions, and workshops of various lengths will be divided into three tracks. During the first session, all participants will have the opportunity to sign up for an individual track after learning more from each presenter about their session.

RSVP is required by June 1st due to building security.

Space is limited.

Light Refreshments will be provided.

Tools/OneSearch

- Using Google Docs and WordPress for Communication and Instruction

Sarah Johnson and Mason Brown, Hunter College - Encouraging Student Engagement in the Library Classroom with PollEverywhere

Emma Antobam-Ntekudzi, Bronx Community College - Not teaching OneSearch is No Longer an Option

Marta Bladek and Maureen Richards, John Jay College - Using OneSearch: Librarians Need to Stop Worrying, Our Students Like It

Anne O’Reilly, LaGuardia Community College

Engagement

- Strategies for Embedded Information Literacy Instruction for English Language Learners

Clara Y. Tran, Stony Brook University, and Selrnsy Aytac, Long Island University - Dis/Information Nation: Voter Personas and Dis/Information Literacy in the 2016 Election and Beyond

Iris Finkel, Hunter College and Lydia Willoughby, SUNY New Paltz

Evaluating Sources

- Navigating between Trust and Doubt on the Internet

Linda Miles and Haruko Yamauchi, Eugenio Maria de Hostos Community College - Understanding Fake News by Teaching with the Game Factitious

Sharell L. Walker, Borough of Manhattan Community College - What Do You Meme it’s Not Credible? Using Memes to Counter Misleading Information

Christina Boyle, College of Staten Island

The Library Information Literacy Advisory Committee, LILAC, is the Library Discipline Council of the City University of New York. All librarians inside and outside of CUNY are welcome to attend the Spring Training.

LILAC Spring Training Committee:

Shawn(ta) Smith-Cruz, co-chair

Daisy Domínguez, co-chair

Anne Leonard

Linda Miles

Robin Brown

Julie Turley

Jonathan Cope

LILAC (UK) 2018 Conference Roundup

I recently attended the 2018 LILAC Conference in Liverpool, England. The conference is organized by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) information literacy group, so they are a bit like LILAC’s sister organization across the pond! There were some fantastic presentations that offered innovative ideas, creative ways to teach IL skills, and many exciting insights about our profession in the ever expanding digital environment. The following are some of my highlights…

Information and Digital Literacy at the University of Sheffield

The librarians from the University of Sheffield described their three year project creating an information and digital literacy (IDL) framework at their institution. The framework echoes ACRL’s framework and threshold concepts, and works to employ active and engaged learning aimed at creating information and digital literate students. The six frames include: discovering, understanding, questioning, referencing, creating and communicating. The literacies help students develop the skills throughout the curriculum and progress from novice to expert during their academic career. The university recognizes information and digital literacy as one of its core graduation qualifications (so lots of buy in) and a means to help provide students gain the necessary skills to be successful in an ever changing digital environment. This fascinating project aligns well with our own mission as information professionals! Want more info? Check it out here!

What Does Embedded Even Mean?

The librarians at the University of Leeds discussed their practice of embedded librarianship and the multiple and unexpected opportunities that arose across campus and within the community. Their presentation offered ideas and inspiration of how to become better embedded and showcased how they embed information literacy skills within course delivery. Examples included: collaborating with nursing faculty in developing and delivering academic assignments to nursing students, offering library support for employees who are part of the university’s local business partnerships, sharing teaching methods with the local National Health Service (NHS) libraries, and supporting students in publishing Open Access journals. The wide range of examples demonstrates the problematic nature of defining what we consider to be ’embedded’, but, it also serves as inspiration that we can embed ourselves across a wide range of places we may not had previously considered, reconsider our pedagogy, and engage students in innovative ways.

Librarians and Students in the Digital Landscape

In his keynote presentation, David White from the University of Arts London, discussed the ‘dataself’ or the ‘technoself’, and how it is essential when teaching students that we position them as a central in their own digital environment and experience. He touched on notions of critical pedagogy in teaching students how to navigate the complexity of the digital environment and expressed great insight into how essential our mission is as informational professionals and librarians. Supporting this mission helps students learn how to navigate the digital landscape, critically question the information that they discover, and learn to maneuver within this stratosphere. As such, we help students understand that the data and information that they interact with impacts their interwoven self-identity. Check out his keynote.

CILIP Redefines Information Literacy

On the final day of the conference, CILIP released a revised definition of information literacy:

Information literacy is the ability to think critically and make balanced judgements about any information we find and use. It empowers us as citizens to reach and express informed views and to engage fully with society.

The revised definition addresses how the theory and practices of information literacy has changed since 2004. In rethinking the definition, they considered the impact on Higher Education, but additionally on all individuals using information. The new definition contains four elements: a high level definition, a secondary statement, contexts, and the role of information professionals. Read more about it here!

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love OneSearch

LILAC has been talking about how OneSearch works and how to teach with it. Based on those conversations as well as on Allie’s presentation to LILAC last fall and just plain old experience, I am ready to tell you How I Learned to Stop Worrying

and Love OneSearch

What is OneSearch is anyway?

We librarians know it as a “discovery layer” and that’s probably not a bad way to talk to  students about it. But it is also really important that they understand what’s in OneSearch. So, it includes what the classic catalog has always had – our holdings! What’s on the shelf in (or checked out from) the library. It also searches across many, but not necessarily all, of our databases. And it includes other stuff too: LibGuides and digital items mostly. This image that no longer appears in the OneSearch landing page may or may not help in understanding that.

students about it. But it is also really important that they understand what’s in OneSearch. So, it includes what the classic catalog has always had – our holdings! What’s on the shelf in (or checked out from) the library. It also searches across many, but not necessarily all, of our databases. And it includes other stuff too: LibGuides and digital items mostly. This image that no longer appears in the OneSearch landing page may or may not help in understanding that.

Background info, Books and Articles all in one place.

For instruction purposes, the filters in OneSearch offer a one-stop way to show students how to see reference entries, books and scholarly (or news) articles all in one place. For example, in a search in the CUNY instance of OneSearch for the term immigration (see it here) you can see that there are reference entries, books and articles. The filters on the right allow the researcher to see just one resource type at a time.

Reference Resources for Topic Exploration

The reference resources filter is a great way to get a list of background articles that provide different perspectives on a topic. In the same immigration search with the Reference Resources filter on (see it here), just looking at those few sources we can already see religion, law, history and child development as perspectives to explore. Sometimes, especially with introductory or composition classes, looking at reference entries first can help students to consider how to approach their topics.

Speaking of Filters . . . .

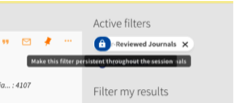

You can “lock” filters in place, which is really, really useful for continued searching/keyword exploration within a single resource type. Once the filter is in place just hover over it and a “lock” will appear; click to set in place.

You can “lock” filters in place, which is really, really useful for continued searching/keyword exploration within a single resource type. Once the filter is in place just hover over it and a “lock” will appear; click to set in place.

Pre-formatted Citations, Ready for Proofreading!

On any record, just click the quotation mark ” to see the standard citation style options. Works best for books and articles, but overall seems pretty accurate. Don’t forget to remind students to proofread these computer-generated citations before handing them in!

OneSearch is the Instant Pot of library databases

Seriously! It does kinda do everything, except when it doesn’t, just like Instant Pot.

Anyway, students are going to ask you this question: Why would I ever search in different databases if I can just search in OneSearch for everything? And sometimes the answer is – OneSearch is all you need. Just like you can use the Instant Pot to cook almost anything.

However, there are 2 main reasons why a researcher might end up at another database instead of (or in addition to) OneSearch.

- Can’t find what you’re looking for. Sometimes OneSearch doesn’t actually provide all the answers, so another database is always a good bet.

- Need more precise, subject-focused research. For example, if you need to use specialized vocabulary such as MESH terms which work great in Medline, but not so well in OneSearch. As well, subject databases allow researchers to find only works written with a disciplinary lens, and that can be tricky to identify in OneSearch since it has so many results.

Basically, it’s one more tool in the researcher tool box . . . or an Instant Pot in the research kitchen!

Open access and ScienceDirect/Scopus

From Elsevier’s newsletter, this article might be useful for teaching and researching:

7 tips for finding open access content on ScienceDirect and Scopus

IL Instruction Overload

As a relaxing summer is behind us and we are in a new academic year, everything goes back to a normal rhythm from Adagio to Andante. That means IL teaching activities pick up the tempo and are likely to accelerate to Allegro as semester progresses.

May I recommend a timely article, “Forty Ways to Survive IL Instruction Overload; Or, how to Avoid Teacher Burnout.”

Like recommended in the article, I sometimes play music by using audio files in PowerPoint to calm down/entertain/relax/wake up/energize my classes, “Sleep Away” at the beginning and “Kalimba” at the end.

Citation

Badia, Giovanna. “Forty Ways to Survive IL Instruction Overload; Or, how to Avoid Teacher Burnout.” College & Undergraduate Libraries (2017): 1-7.

ABSTRACT

Teaching information literacy (IL) sessions can be emotionally exhausting, especially when faced with a heavy instructional workload that requires repeating similar course content multiple times. This article lists forty practical, how-to strategies for avoiding burnout and thriving when teaching.

URL

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10691316.2017.1364077